Jerry Coyne takes down Ross Douthat’s New York Times column in The New Republic along multiple dimensions, but perhaps the most interesting one is his draw-down of the question of what exactly Christian morality amounts to? We can equally question any other religious morality or even secular ones.

Jerry Coyne takes down Ross Douthat’s New York Times column in The New Republic along multiple dimensions, but perhaps the most interesting one is his draw-down of the question of what exactly Christian morality amounts to? We can equally question any other religious morality or even secular ones.

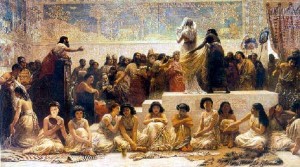

For instance, we mostly agree that slavery is a bad idea in the modern world. Slavery involves treating others instrumentally, using them for selfish outcomes, and exploiting their human capacity. Slavery is almost unquestionable; it lacks many of the conventional ambiguities that dominate controversial social issues. Yet slavery was quite acceptable in the Old Testament, with the only relief coming for the enslavement of Jews by Jews with the release of the slaves after six years (under certain circumstances). Literal interpretations of the Bible resort to expansive apologetics to try to minimize these kinds of problems, but they are just the finer chantilly skimmed off human sacrifice, oppression, and genocide.

So how do people make moral choices? They only occasionally invoke religious sentiments or ideas even when they are believers, though they may often articulate a claim of prayer or meditation. Instead, the predominant moral calculus is girded by modern ideas and conflicts that are evolving faster than even generational change. Pot is OK, gay marriage is just a question of equality, and miscegenation is none of our business. Note that only the second item has a clear reference point in JCM (Judeo-Christian-Muslim) scripture. The others might get some traction using expansive interpretations, but those are expansive interpretations that just justify my central thesis that moral decision-making is really underdetermined by religious thinking (or even formal philosophical ones). Moral decision making is determined by knowledge and education in an ad hoc way that relies on empathic and intellectual reasoning.… Read the rest