Sylvia Plath has some thoughts about pregnancy in “Metaphors”:

I’m a riddle in nine syllables,

An elephant, a ponderous house,

A melon strolling on two tendrils.

O red fruit, ivory, fine timbers!

This loaf’s big with its yeasty rising.

Money’s new-minted in this fat purse.

I’m a means, a stage, a cow in calf.

I’ve eaten a bag of green apples,

Boarded the train there’s no getting off.

It seems, at first blush, that metaphors have some creative substitutive similarity to the concept they are replacing. We can imagine Plath laboring over this child in nine lines, fitting the pieces together, cutting out syllables like dangling umbilicals, finding each part in a bulging conception, until it was finally born, alive and kicking.

OK, sorry, I’ve gone too far, fallen over a cliff, tumbled down through a ravine, dropped into the foaming sea, where I now bob, like your uncle. Stop that!

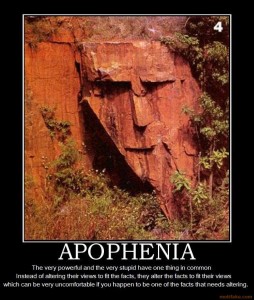

Let’s assume that much human creativity occurs through a process of metaphor or analogy making. This certainly seems to be the case in aspects of physics when dealing with difficult to understand new realms of micro- and macroscopic phenomena, as I’ve noted here. Some creative fields claim a similar basis for their work, with poetry being explicit about the hidden or secret meaning of poems. Moreover, I will also suppose that a similar system operates in terms of creating networks of semantics by which we understand the meaning of words and their relationships to phenomena external to us, as well as our own ideas. In other words, semantics are a creative puzzle for us.

What do we know about this system and how can we create abstract machines that implement aspects of it?… Read the rest